- Article

- Read in 65 minutes

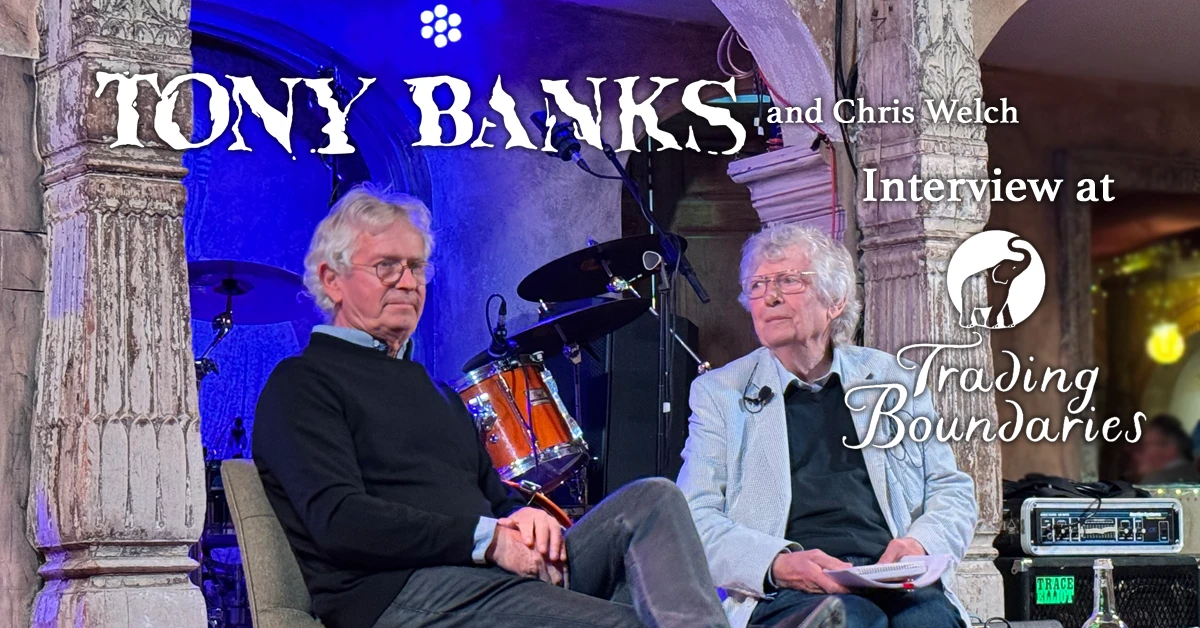

Tony Banks – Q&A with Chris Welch at Trading Boundaries 2025

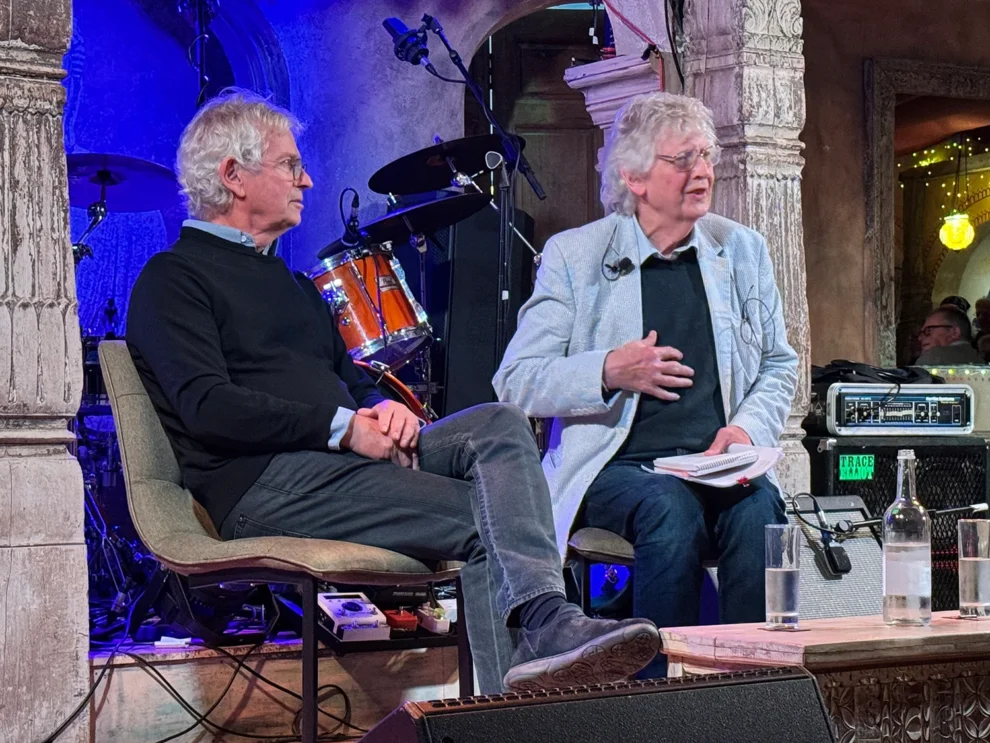

On November 14, Tony Banks was a guest at Trading Boundaries in the UK for a stage interview with Chris Welch. We have edited the interview for you.

Trading Boundaries in East Sussex has become a real cult club over the years. It is small, and performances there are always accompanied by dinner and approachable musicians. Steve Hackett has been a regular there for years. He has also dedicated his live album Live Magic At Trading Boundaries to the club. In addition, there are many other interesting concerts from the Genesis scene. This includes the performance by Rocking Horse Music Club, with songs by Anthony Phillips and Mike Rutherford in 2019.

Rocking Horse Music Club played there again in 2025. The album The Last Pink Glow, released 2025, famously included a song co-written by Tony Banks. He also plays the keyboard on the track. Tony Banks was at Trading Boundaries that evening, but not to play live. He answered questions from fans during a stage interview. The interview was moderated by none other than journalist Chris Welch.

The following interview is based on a transcript by Stefano Tucciarelli and was edited by Christian Gerhardts and Paul Kingsbury.

Speaker: Good evening. Good evening, everybody. On behalf of all of us here at Trading Boundaries, I'd like to welcome you here. So, we have two legends really in their own genres about to join us on stage. First of all, Chris Welch. Many of you will have read his words. Maybe you've read one of his 40 books, or maybe you've read his columns that have been in Melody Maker since '64, or many, many, many other outlets since then. He really, really knows his stuff and it really genuinely is an honor to have him here this evening.

He will be managing a Q&A after the main discussion. There will also be a few minutes to ask a handful of questions for the audience. And then our very special guest this evening. Now this is where I genuinely have to pinch myself. We have these moments at Trading Boundaries and it just, everything is so worthwhile. I know I'm in very good company when I say every so often somebody comes along and their music becomes the landscape of your life, and tonight is absolutely no exception. So, along with Chris Welch, please give a very, very warm welcome to Tony Banks.

Tony Banks: I should explain, I'm Tony Banks. But Chris, what a guy. Am I interviewing you or are you interviewing me? I'm happy to have you interview me. When did you first start working on Melody Maker?

Chris Welch: Yes. I had the job of the lifetime working for Melody Maker. Before that, I used to edit the school magazine. Then I got the job here in Fleet Street working at The Scotsman Newspaper, where I was the tea boy. I wanted to be a reporter, but they gave me the job as a tea boy. But that was a great experience and I actually published my first article, which was a review of Louis Armstrong at the Gaumont State in Kilburn, and that was my first story in print. I got a job on the local newspaper and our local band was The Rolling Stones, so, there you go.

I started writing about The Stones and people said, "Well you should work for a music paper." So, I sent my cuttings to Melody Maker, they gave me an interview and then I got the job, 1964. And the marvellous thing about working for Melody Maker, it was the musician's paper. We were supposed to encourage, whether it was jazz, rock, or folk music, we covered everything. And so my part really used to go around. I spent all my night drinking heavily in nightclubs, which was great, and rock concerts. That's why I'd see all the new bands like the Yardbirds, Spencer Davis Group, Georgie Fame and The Blue Flames. And I'd write about them.

And then one day, one night I went to Ronnie Scott's club, and upstairs there was this remarkable band playing. I think Roger Dean had designed the upstairs room at Ronnie Scott's. I was with Peter Frampton, we'd been drinking probably. And he said, "Let's go and see this band." There's this extraordinary band playing upstairs. There's the man playing the bass drum and singing, and I later discovered of course, that was Peter Gabriel. And that was the first time I saw Genesis in action.

Tony Banks: I think playing the bass drum is a little complimentary about it. He certainly had one, yeah!

Chris Welch: So, do tell me how Genesis got together. How did you end up at Ronnie Scott's Club playing that night?

Tony Banks: Well, we obviously got together originally at school. Peter Gabriel and I were sort of best friends in our later days at school. Anthony Phillips, who was the original guitarist, and Mike Rutherford were good friends and Ant wanted to make a tape. He asked me if I wanted to go along and help him out. And I said, "Yeah. So why don't Peter we come along and we'll do our song as well?"

When we went there, initially Pete didn't come the second day. So, the first day Anthony decided he was going to sing his own song. And I said to him, I said, "I think you should wait till Pete comes. It'd be worth doing it, it'd be better." And then when Pete came, we then did the rest of that thing. That, sort of, gave us an amazing amount of confidence. It didn't go anywhere at all, but we sent the tape to, or managed to get the tape to Jonathan King, who at the time was a notable in the music business, and he liked what he heard enough to fund us for the next period.

But I'll have to come back to you on my first time with Genesis. Because the first time Genesis was a review in Melody Maker of our first single called The Silent Sun, 1968. I was 17 when that came out I think. I had a phone call from Richard Macphail, who I'm sure many of you know, to tell me what was in it. He said, "I'm going to read it to you on the phone."

I'm very young and I'm thinking, "This is my big moment."

And he said to me, and he read out, he said, "Dear, Jonathan King. This recording, Sir, is muck. You have befitted on the world a work so impoverished of art as to be quite unpalatable." I'm very young and I'm thinking, "This is my big moment." It's all over, almost before it started. Chris Welch, who we admired a great deal at the time, hates it. And then he apparently then it changed and it said, "Swounds man, I'm jesting. 'Tis sorry sport to make satirical pokes at one of the better songs of the week. By all that's happy, a great hit."

Well, you weren't right of course in that sense, but at least you ended up. But it was a very profound moment. That's why I remember it so clearly. I don't tend to remember things very well actually. That is imprinted on my brain! When Richard read it out to me it was kind of like – I thought that's it.

Chris Welch: I'm sorry about my introduction.

Tony Banks: I'll come back to Ronnie Scott's now. Well, basically what we had in a period of time when we first started playing on the road, what you wanted to try and do was to get in the back pages of Melody Maker and appear to be working a lot. So, you played these shows, you had a couple which were reasonable ones, and then you'd throw in a few others. And we managed to get what was called a residency at Ronnie Scott's upstairs, the jazz club, which was obviously a famous club. Upstairs was their attempt to doing something slightly different.

I don't think we ever had more than three or four in the audience. Mostly we knew the people there. But it was profound for us because in that place, Tony Stratton Smith, who was the boss of Charisma Records, came up to see us having been advised to see us by John Anthony, who managed, produced Rare Bird at the time.

He liked what he heard, and he started the record label and was probably desperate to fill it with any bands he could find, and we fitted the bill. And so it was a very important moment for us really. But to be honest, from the point of view, we learnt a lot playing there. One thing we did learn was that it didn't really matter if you didn't have any lyrics to your song, because no one could hear them anyhow. We had this one song, called "I've been travelling all night long", at least that's what we called it at the time, which poor old Pete, you know, he was mouthing his way through it. No one cared, but it taught us how to play. It was early days for us playing a short time.

Chris Welch: Charisma were actually were very good to the band. Oh no, it was Decca actually at first, wasn't it?

Tony Banks: Decca weren't very good to us, but with Jonathan King, we were on Decca when we did From Genesis To Revelation. With Jonathan King, he was very good to us. We made three singles with him and the album was From Genesis To Revelation, and he backed us all away. The album, I'm afraid did nothing, did anything.

And so we got decided that we would go, Ant in particular, was very keen to play live. And so we decided we'd have a go. Started rehearsing and writing music of a different kind, trying to go a little bit further with everything we did. Initially, I think Peter and I didn't think we would stay with it. We knew that Ant was keen and Mike was keen to do it with it. But after a period of time, when I suppose when I was supposed to be going back to university, I decided that, you know, chances like this only come up once or twice and it was starting to sound really interesting. So, I took a year off university in order to see how it went.

Chris Welch: You then studied chemistry.

Tony Banks: I studied physics. Well chemistry initially then I was switched to physics with philosophy actually. After a year when the band had actually done nothing at all, I still decided not to go back, and they let me take another year off actually. I've never had a problem ever since on that score. I kind of presume I'm still taking years off, but anyhow, it was the decision I had to make.

Mike always says that I couldn't bear the idea of the band being successful without us, without me, which is probably true, because Ant had a friend called Harry Williamson, who was a good keyboard player who was lined up to replace me and I thought, "I don't know if I can take this." I loved the music and we were writing some interesting stuff at the time – the beginnings of what became Trespass and various other bits.

I thought this was something I really wanted to do. The idea of being in a band was a sort of impossible dream really. But when I was younger I never thought you'd do this, particularly from our background. We came from a fairly traditional middle class background and it was not what you were expected to do, but something had a chance. There's a real thrill to be able to try and do it.

Chris Welch: Because you'd had piano lessons from an early age. Talking about Melody Maker, it was great source of jobs for musicians, wasn't it?

Tony Banks: Well, it was the back pages of Melody Maker that were very important. Because as I said, if you weren't actually doing much, you needed to look like you were, and we did some incredible shows. The best probably we ever did, it was a club in Beckenham, where it was a dance place really. But on Mondays they'd have a progressive night. So, we went up there as a band and there were two girls, who sat right at the back. That was the audience. Peter said to them, "Why don't you come up to the front?" The last thing they wanted to see was band like us, I promise you. He said, "Why don't you come up to the front?" He said, "I'm Peter, that's Tony, that's Mike."

And the poor girls had to sit there while we played our show, which was – well we got a fiver- that was the important thing. But some of the shows were like that. You had for the shows that the agent had found for you and you did some, which were good, some were bad. Often the ones that paid the best were the worst shows actually, but that's another story.

Chris Welch: It's an extraordinary thing to think about how many of our great wonderful bands that we all idolize now, they had to go through these early stages and suffer.

Tony Banks: We suffered terribly, it was hard. We always seemed to feel we were on an upward spiral. And you went to shows, we played with lots of the groups of the era, we supported a group like Mott the Hoople, who were very supportive to us actually. And then the next time a month later we'd go back to the same venue and play as headliners. So, that was all quite exciting really, so you felt the steady build.

We had a few clubs, Farx, we mentioned them, and Friars who were very, some of the common, became big enthusiasts of the group. Meanwhile, the other thing that was helping us a little bit was for some reason or other we were very popular, the album Trespass, did very well in Belgium, and this gave us a lot of interest.

We went to Italy, we topped the bill. So, that was quite exciting.

And then the next album, Nursery Cryme, was very popular in Italy. We actually went to Italy and were playing big places, really big places, thousands of people. And then coming back to England and playing, you know, 20 seaters. So, it was a strange experience really. When we did a tour in '71 or '72 with Van der Graaf Generator, Lindisfarne, I think it was. In England, Van der Graaf were top of the bill.

Went to Italy, we topped the bill. So, that was quite exciting. So, it was a sort of steady build and we had started to have very minor chart success with the third album, whatever it was, Foxtrot, and so it built up.

Chris Welch: Of course, you have all these colourful arrangements – there were some amazing arrangements that the band worked on together.

Tony Banks: I think what appealed to us really was not … non-repetition in trying to tell a story with a song. So, you wouldn't necessarily have a verse and chorus, conventional. You'd start it with a bit and go somewhere else and see where it led you. I don't know. It seemed to work for us that and you could build up. I think with something like The Musical Box, its real peak is the final section which you build up. You need to have all the stuff before it in order for it to work I think. That was something we were pretty proud of at the time. Actually it's one of those examples where I thought I'd written a great organ bit, and that's good enough.

And then Peter started just singing on top of it. I thought, "You bastard, you're singing." And then it was this, "you stand there with your fixed expression" section, which of course after I heard it I thought this is actually brilliant. And so I kind of you know warmed to it.

Watcher Of The Skies was a classic moment of the time with the mellotron.

Chris Welch: Did you find that using a range of keyboards, like almost an orchestral effect, that gave Genesis its sounds? You have the Mellotron…

Tony Banks: It was an important aspect of the sound. We were a group. I think the nature of keyboards at the time, obviously piano, organ, then the Mellotron in particular, were very distinctive things. The chords, I'm known for my chords, and that was very much a part of the early Genesis thing – the opening to Watcher Of The Skies being a classic moment of the time really with the Mellotron. Which was a curious thing really in many ways because although the first two chords I played them and they sounded fantastic. I thought it's great.

I then tried to write chords afterwards, and because of the nature of the Mellotron, I was using brass and strings at the same time, so out of tune. There were lot of chords I wanted to play, I couldn't play, so I had to make it out of chords I could play, and it obviously worked and it was a very dramatic moment..

It was a great stage moment. Peter came out with the mask…, the red thing on and with the UV, the batswings actually, going back an era, with the ultraviolet stuff. It was also one of the first times I think that a group had ever done, we put the Mellotron out the PA in stereo. Up to that point, as far as I know, groups had only ever put the vocals up in the PA, it was a different era. I think it just stunned people that you came on stage with something that's incredibly wide sound with a piece … the makeup and stuff. And also we had this gauze curtain behind that hid all the gear, which again was very against the tide. Most groups liked to appear with as many Marshalls stacked behind them as they possibly could. Half the time they had nothing in them actually.

One group we played with, I remember looking back, there's just one speaker wired up, all the rest were just boxes. But no one really knew, because they sounded loud.

Chris Welch: That's terrible. That's the Marshall Wall of Sound.

Tony Banks: Yeah, that's right. Well, that's what they advertised themselves with. They probably sold the boxes. A bit like burglar alarms you know – as long as you've got the signup, no one really bothers to check.

Chris Welch: Just briefly on the Mellotron, it did produce an incredible eerie sound, that I'm sure all Genesis fans remember, wonderful sound on the Mellotron.

Tony Banks: Well, it was at the time not many people were using it. It was obviously the King Crimson, In Court Of The Crimson King was a notable moment, and that was quite influential on us in those early days. I wanted to use one and I used it on what we borrowed. I used it on Visions Of Angels on Trespass, but wanted to use it further than that. On Nursery Cryme it became a very big feature, particularly on The Fountain of Salmacis. You could do these great big string kind of crescendos and stuff and I just found that really exciting.

Chris Welch: Another great trend, Supper's Ready, which is on Foxtrot, wasn't it?

Tony Banks: That's right. Supper's Ready was I think probably the best thing we did during Peter's era, and it was the longest as well. Whether there's any connection between that, I don't know. It started off a bit like Musical Box. I had this guitar sequence, that I was rather proud of, actually. We then used that as a basis and put a melody on top of it, and that became the first bit. And then we started improvising a bit doing bits and pieces after that and it developed.

It was going quite nicely, but it was turning a bit into Musical Box part two, so I just said: Peter has this great song out which was done as an item on its own, which was Willow Farm. I thought it would be just great to go into that. It was a really pretty bit, that sounding really nasty and it was such a great effect that, and it really taught us a lot. And then once we did that, got the drums and the big keyboards involved, it was then after that it just developed into the thing. I think the final section was the Apocalypse In 9/8 leading into the final section. It was a very strong moment.

Chris Welch: Were you influenced in any way by any other groups at all?

Tony Banks: Well only initially. Obviously you've got to mention the Crimson thing, but at the time after that we didn't really listen, they were all the competition, hated them all. Yes, who seemed to be very successful.

Chris Welch: Now it can be told.

Tony Banks: No, we were still very influenced probably what we liked in the '60s, which was started with The Beatles very much, and in my case, The Beach Boys and Simon and Garfunkel. And then some of those late groups, '60s groups like Family and Fairport Convention, Procol Harum. I think they all gave us an idea that you could go a bit further, and that's what we decided to do, to run with it, and seemed to, managed to get an audience that wanted that as well.

Chris Welch: Just one funny story, when I first started seeing the Genesis, I saw you at the Friars, Aylesbury. When I arrived, I was a bit late, the audience were booing, they were booing the band. It's just terrible. What are you booing for? The music's wonderful. And it turned out, Peter …

Tony Banks: It was a terrible idea actually. Pete said, "Just for tonight, why don't you boo every time you like something." It was so depressing because even though you knew it was kind of enthusiasm, it didn't work. Because normally for us Friars was fantastic and for us and that particular night was a bit strange.

Chris Welch: I felt for you, I really thought they were booing.

Tony Banks: They were.

Chris Welch: But you had a succession of hits after that, didn't you? It built up to the first hits, singles.

Tony Banks: Well, we didn't really have any single hits at all. I mean, I Know What I Like did end up on Top of the Pops being danced to by Pan's People, or whoever it was at the time, which was a kind of a curious moment. But we were a little bit, I think we were a bit too precious in those days. We decided we're not going to do Top of the Pops, it's just not for us.

Chris Welch: Phil liked Pan's People. He told me!

Tony Banks: Nothing against Pan's People, I enjoy watching them myself. But it was a strange thing to do because it's not really the thing that lends itself to any dance music. That did help a bit, I remember Selling England By The Pound, which was the album it was off, did a bit better than the previous ones.

I Know What I Like was Steve's riff and it's a good feel song.

Chris Welch: But the famous cry, it's one o'clock and time for lunch. 1:00 indeed time for lunch. I kept saying it every day.

Tony Banks: Well it was good. It was a good little good song, great little riff, it was Steve's riff, and we then developed it into a song and we kept it simple. It just seemed to be right to keep it simple. I Know What I Like was inspired by the album cover, and it produced I think a song that over the years we've always played really because it's a good feel song.

Chris Welch: Talking of album covers, Genesis' album covers in the '70s were quite outstanding.

Tony Banks: I think Selling England probably being one of the best. It was done by a real artist, Betty Swanwick, who's someone I quite admire anyhow. And then the ones we did with Hipgnosis, particularly The Lamb, Wind & Wuthering, and A Trick of the Tail are all nice I think. We've had some good ones, we've had some less good ones too. I'm not sure about And Then There Were Three. Or the one with … Genesis, it was called.

We couldn't think up a title, we couldn't get a very good album cover out of it, it's got good songs on it, but it just wasn't our best moment for album covers. But no, we always tried to get something that reflects the feel. That's why Abacab really worked well for us because the artwork was not airy-fairy like we'd done in the past, and the album was supposed to be something a little bit different.

Chris Welch: I remember going to see for Melody Maker all the Genesis shows in that period. And I loved the Rainbow Theatre and Drury Lane. I met somebody here tonight and he said that he was at Drury Lane when you did two nights there.

Tony Banks: Was it the night when I stopped playing the introduction of Firth of Fifth, which I used to play in those days. But I had to do it on an electric piano and the nature of electric pianos, you couldn't go to the high octave, I had to drop an octave in the middle.

One night I was playing it and I thought this is going quite well, it sounded quite good and I thought I'm on the go now. I had no high octaves to go to so I just stopped like that. It was very embarrassing. The band just looked to me like this, and Phil went……… THREE, FOUR, drum roll, and started the song.

And what was rather sweet was: my father, who was very unmusical – used to wear earplugs for everything – he thought I was taking a bow.

So, after that I got a bit nervous about playing it after that. I have to say it was very difficult to play on an electric piano because it's got no touch and so it was a bit weird.

Chris Welch: Did you have to carry the gear yourself or did you go and put it on?

Tony Banks: No, we had a road crew by then. Yes, in the early days we did our own thing. I was actually quite good with the soldering iron. I did a lot of rack jack [?] leads and stuff.

Chris Welch: There you go, that's the secret of Genesis, a soldering iron.

Tony Banks: It's a very important thing actually. Ant always seemed to manage to end up just taking the gear in and he was just carrying a plectrum – he thought that quite was enough for him – needed to protect his delicate fingers.

Chris Welch: Of course also Drury Lane, that's when Peter did one of his famous stunts, wasn't it, do you remember? He came flying in the air.

Tony Banks: We did that at for the whole of that tour, I suppose it was the Foxtrot tour, I can't remember where. In the air he would, having been be in his black costume, he'd come out at the of Supper's Ready after the keyboard solo, dressed in this silver gear with silver make-up on and all the rest of it. And then he'd be on a pulley and he'd get suspended in the air and would do the last part of the song. Most of the time it worked really well, but there was one time when he went round backwards, he was facing back to the audience and he was desperately trying to wheel it round so he could sing into the thing. That's the trouble with those effects, particularly in those early days, it wasn't very sophisticated.

Chris Welch: Painful.

Tony Banks: I don't know, it was an interesting moment.

Chris Welch: But then of course came The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, which was an epic album full of really good, interesting ideas, but a little bit controversial would you say?

Tony Banks: Yes. After Selling England By The Pound, which had gone down quite well, The Lamb didn't go down nearly as well, the double album. I don't know what people quite made of it. I think we struggled a little bit because when we first played it live, we wanted to do the whole album which we thought that would be nice to do. By the time we did it in America, the album wasn't released. So, we were playing a whole hour and a half of music people had never heard before, and it was a little bit strange and I don't think the audience were quite ready for that.

As the tour went on and people got to know the record, it went down a bit better. But it was a strange thing, because we always had songs on records that we didn't play live, because they didn't work very well live, difficult to play whatever. Yet from The Lamb we wanted to do every song, and I think a few of the songs we would never have chosen to do had they not been part of the thing. So, it was down moments. It was a strange tour because Peter was coming and going a bit, and the final shows we played in Besançon in France.

We ended on a bit of a whimper with the Lamb tour

It was pretty bad and the audience was not very interested in it and it didn't go down very well. We were supposed to do the final show in Toulouse and we cancelled it because we couldn't face it because it wasn't very well attended. We ended on a bit of a whimper with that tour. It was strange really. It was not my favourite tour to do by any means for it, so it's always coloured the whole album a little bit for me.

But it meant that when we did later, obviously once Peter was no longer with us, and we decided to do another record, it meant that we could go back to a single album and do slightly more songs that were more straightforward perhaps, and less involved with the story and the sort of dark edge that Lamb had. Which also I liked a lot actually, but it was just meant it was one thing. Whereas with A Trick Of The Tail, we were able to go to a more balanced sound like we had on Selling England.

Chris Welch: The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway has been re-evaluated in later years by critics.

Tony Banks: Well, yes, it's become iconic. Obviously we have been involved in the remix of that recently with Peter down at Real World, which was great fun for us just to go back over it all and listen to the stuff. We were really impressed actually, thought this sounds good. Because at the time you're doing it, you're never quite sure, there's things you're compromising all the way and things are happening, and you're not listening to it in the same way that an audience does.

But I think there's some really good stuff on that actually. I just never felt it ended very well. There's nothing wrong with it. It's all right as a track, but it's not an ender. The way that Supper's Ready had ended – such a climax and had been such a strong thing – I felt it missed out a bit on that.

Everyone says it would make a great single album, but no one puts the same tracks on. That's the point. But I think Peter singing on something like Back In New York City is extraordinary, and I just said to him, "We should do that now because you sing like that, only if you took it down about an octave, I think."

Chris Welch: There have been changes in the line-up of Genesis. I think Melody Maker played a constructive role in that.

Tony Banks: Did you?

Chris Welch: Yes. I said fire him. But recruiting people through ads in Melody Maker?

Tony Banks: Yes. Well, they were so good that we didn't employ any of them, as was pointed out. Yes, we saw lots of people. We auditioned people after Peter left with the idea that we get another singer in. No one really fitted the bill, and Phil tended to demonstrate the songs to the person so that they could get an idea what they're supposed to do, and he sounded pretty good.

And then it kind of, it got to the stage where we thought we're not going to find anyone. We tried some poor chap doing Squonk in the studio. It was completely in a wrong key for him and it sounded awful. It was a shame because he had a good voice. But anyhow. So, we'd always thought that Phil would probably sing things like Mad Man Moon and Ripples because they're soft songs, he had a very soft voice in those days. But he said, "Let me try Squonk."

So, he got in there and it actually sounded pretty good. I don't say he was as good as he got later, but he sounded pretty good. So, we thought, "Well that's going to work, let's do that." Did the album. Then we thought we have to get a singer for live, and Phil would never want to leave the drum kit. Anyhow, as it turned out, he said, "Well, let me have a go."

So we went with Bill Bruford and it was extraordinary!

I wasn't sure actually, because I got so used to Peter, who had a presence that I got used to, and Phil was the drummer. So, anyhow, we worked out a compromise where we got Bill Bruford in as the drummer. He was someone that Phil really admired and we all liked very much. And so we went on that and it was extraordinary. Because the first time we played this show in London, Ontario, Phil was out there at the front and I thought, "This is really weird. It's like going on stage with no clothes on."

I got used to seeing Peter out the front there and being very confident in what he could do. And he always looked a great presence, was a great singer. Just after a song or two I thought the audience really like him and this is going to work. After that first tour show, I thought, "This is fantastic. This is going to work and we can carry on," which is what we did obviously with albums after that.

The idea of Phil as a singer, although it seems very obvious now, it was not obvious at the time at all really from anybody's point of view, including his own. I think I was amazed when he said he wanted to give it a go because he'd drummed forever. That's what he wanted to do, just drum. But I think the fact that he could do some drumming and do a certain amount of double drumming with Bill was really solid.

Chris Welch: I remember seeing Phil when he first came on stage at the Odeon in Hammersmith, I think it was, and he wore a flat hat.

Tony Banks: That was Say It's Alright, Joe. It was a vague attempt to do a little bit of costume stuff. Peter had done all these flamboyant costumes and stuff and so Phil's idea of a costume was to put a flat cap and a raincoat on for Say It's Alright Joe. It seemed to work for him, so that was okay. But we decided at that point we'd take the emphasis a bit off what Peter's character, because he was doing what he did. And we used Phil with slides behind and much more subtle lighting, which obviously over the years got more and more subtle. Sorry about that. I don't know, you make up your own jokes, it's okay.

Chris Welch: There was the album And Then There Were Three, which is when you had to find a new guitar player, as Steve Hackett left.

Tony Banks: It was a strange thing really with Steve. Steve's role within the group grew over the years really, because in the early days, he and Phil were junior members I suppose, but after Peter left, he became more prominent. Particularly Wind & Wuthering where he wrote a really beautiful song Blood On The Rooftops, which was mainly him and Phil's chorus, but the rest of it was him.

It was strange at that point that he decided he was going to leave. We were mixing the live album Seconds Out when he came around and well, Phil met him on the street actually. Said, "Do you want a lift in?" And he said, "No, no, I'll come in moment or something." And then later he just phone up and said, "I'm not coming in." So, it wasn't great to be honest, but we decided after that that we probably would try and do it as a three-piece.

Mike was learning as a lead guitarist and he was very much a rhythm guitarist, obviously he was very crucial to all that stuff, and we said give it a go. And obviously on And Then There Were Three, I think, Phil by that time was developing into a pretty accomplished singer I think. Mike did a pretty good job on guitar, I think.

After And Then There Were Three, Mike developed into a very fine lead guitarist.

He wasn't kind of able to be as fluid as Steve had been at all at that point. But things like the song Burning Rope, for example, had a guitar in the middle, which basically I had written. I know that if Steve was still with the band it would've developed more and probably be something slightly more exciting maybe, I don't know. But it worked pretty well, and so that meant that we could do it. And then after that, Mike developed into a very fine lead guitarist and so from then on with Duke, which is always big. One of my favourite albums was the one that came after that. I think we were all playing really well as a band. As a three-piece we just really seemed to gel.

And then There Were Three was probably the album that it's in between albums. It's got some lots of lovely songs on it, but I don't think it was as good as the albums on either side of it.

Chris Welch: Thing about Mike was he had a very cool sense of humor and manner. I remember interviewing him in Tokyo on the top floor of a hotel, Hilton Hotel. And suddenly all the ceiling began to quake and the chandelier broke and fell down and he said, "I think that was an earthquake." He'd be very cool.

Tony Banks: Well, Phil, obviously when we first hired him, he was very funny. He was very good at telling jokes and all the rest of it, and he thought he'd got the gig on the strength of his telling jokes. So, every time we picked him up to go to a gig, he'd work out a few jokes to tell us when we were in the car. Which was totally unnecessary of course because we thought he was a wonderful drummer after one go. But he was a very light presence, which us being rather, particularly me I suppose, rather heavy types. Peter and I were best of friends, but we could certainly argue if we wanted to, and he could lighten it up a bit sometimes.

Chris Welch: The 1980s really was, I suppose you could say the golden years in a sense for success of Genesis, because you had a string of albums, lot of hits.

Tony Banks: We got lucky with the MTV world really. We seemed to … sort of … just at the right moment. Phil obviously was a great performer, which helped a lot. Mike and I, not so, but you put a hat on, false moustache, it's amazing what you can get away with. And so I loved doing those videos actually, it was great fun actually..

Chris Welch: It was very funny, yes.

Tony Banks: Some were pretty bad, but some were really good, I think. I'm particularly fond of the video Keep It Dark, which I thought was one of the best videos we did. I like the contrast between the verse and the chorus, but you did these things. Obviously we had great fun with Jesus He Knows Me having the middle eight, we said, "we want to do one video please with lots of pretty girls in bikinis, we want to do this." So, it seemed to be because it was like all these other groups went.

Chris Welch: You don't want to leave it too late.

Tony Banks: Yes. Anyhow. So, it was gone with the essential, the build of that song, which was all about corruption, televangelists and everything. It seemed like a very good place to do it and so we did it.

Chris Welch: Brilliant. And Invisible Touch 1986 was a blockbuster album, wasn't it?

Tony Banks: It did very well. It provided us with our first and only number one in America in terms of singles, which of course was knocked off the next week by Sledgehammer. It was a little bit jading. But anyhow, there you go. At least we made it there before him. But we were lucky, with that album. There were singles. We were able to release about five songs off that as singles which were all hits in the States.

They weren't really over here, but there's a different attitude. Because American singles, if they got a lot of radio play, that meant it always got in the charts. So, we had Tonight, Tonight, In Too Deep, Throwing It All Away and other stuff all did very well. And so the album was commercially our biggest success at the time, particularly in America where it did really well.

Chris Welch: Was it number one for three weeks?

Tony Banks: The single was number one in America for a week. The album wasn't, but it did sell very well every year. It was an extraordinary time for us, it wasn't what we'd expected in a way. Something seemed to take off. We weren't obviously harmed by the fact that Phil was having commercial success on his own, but it was happening despite that, I think in a way.

When you looked at the music with any depth, it was pretty different. But it had obviously the fact that Phil was a big single success was not doing us any harm, I can't deny that. But he opened a lot of doors for us and for those two or three albums we did in the '80s from Duke onwards through to We Can't Dance, it was just fun. You went out there and suddenly everybody liked you.

Chris Welch: And you did one of the world's biggest tours at one point, didn't you?

Tony Banks: Well, it was soon broken. We did the most nights at Wembley Stadium, which was broken the following week I think by Michael Jackson and broken again by Madonna. It's not like Coldplay who plays there for what, six weeks? It's perspective. But no, that wasn't really what we were after, but it was extraordinary. You just weren't expecting it. The Invisible Touch album in England was in the top 10 for about a year, and it was so different from what we'd experienced the '70s. All those albums had spent one or two weeks in the charts.

Chris Welch: Far cry from upstairs or Ronnie Scott's Club, I think.

Tony Banks: I'm not too sad about that actually. It was fun to have done those things. You feel you've earned it a bit. I think it's difficult, I don't know what it's like for people now, but there was a period where people could come in at quite a high level quite quickly. They'd have a hit single or something and then you have to try and do the show. We had 10 years of learning how to do it before we had a serious hit single which was probably for me, I suppose is the first proper hit single we had and we were ready for it by then.

Chris Welch: You had the opportunity to record your own solo albums as well.

Tony Banks: I did.

Chris Welch: Did you enjoy doing that because it was the freedom?

Tony Banks: I loved making them. I never really enjoyed putting them out because it was slightly disappointing. No, and I did, at the time, I did A Curious Feeling, it was the first one, it was after Wind & Wuthering. And I thought what I'd had with the song One For The Vine, which I was very proud of at the time, I would extend this idea of that story over an album.

And that's what I did with A Curious Feeling, and I always thought it sounded pretty good. It's one of those things you put it up, it came out while we were actually writing Duke, and it came in at number 20 in the charts. This is happening, next week it was 21, and after that it disappeared completely. And then of course about a month later, Mike's album comes out and it's number 10 in the charts. And so it was after that and it was Phil who moved us out that market. It was before Mike and The Mechanics, this was his first solo album, which was a nice song. So, I think it did affect things a little bit. I expected a larger amount of the Genesis audience to follow me into the first album, because it was a very Genesis-like album.

Chris Welch: You sang on The Fugitive?

Tony Banks: I did sing on The Fugitive. Lots of reasons for doing that. One was having done A Curious Feeling, there was always a little bit of an identity problem because I wasn't a singer. I got a lovely email, a lovely note actually from Pete Townsend, it was written on bog paper. He said how much he liked the album and how much he liked my voice. I didn't have the heart to go tell him that I didn't sing it. I didn't say that.

Anyhow. Actually, I met him over a few years later after, and I mentioned it and he said, "Why the fuck didn't you answer me?" And I said, "Because you praised my voice so much." Anyhow, that was quite funny. But then with The Fugitive, I thought, "Well, I'll give it a go."

I'd sung a demo version of Keep It Dark, which it actually sounded all right. I thought it actually sounds okay, I could do this. And I thought, "I'll give it a go and see what I've been putting these people through all these years." Tried to keep the songs a little bit more straightforward so I could sing them, and you won't have the identity problem. I did the thing, I was pretty pleased. Stiff Records, strangely enough, were very interested in releasing it until they met me.

Chris Welch: What happened?

Tony Banks: I turned up in my big coat and my scarf and long hair and I wasn't really what they were after. Stiff Records at the time was very trendy and hip, and Madness was their key thing at the time. But lots of people know, I don't really like Madness, so I was quite happy with all that side of it. It wasn't as much punk as it's just music, slightly more direct music again. They liked the album and everything, but they couldn't take me. They couldn't do anything with it, they didn't know where to start, which bit would they cut off first. So, I went back to Charisma, who are obviously … Tony Stratton-Smith …, very nice and had me back and put the album out and of course it didn't do anything.

But I think it's something about singing your own songs, even if you're not the greatest singer in the world. Let's face it, there's a lot of singers out there who aren't great singers. Bob Dylan, Bob Geldof comes to mind, people who haven't really got a great voice, but when they sing their own stuff, it just somehow really works. I think there are one or two moments on that one which worked like that. And there's something about that personal quality I quite like.

Chris Welch: Would you have liked to have sung live on stage?

This Is Love wasn't the greatest video, but it was okay!

Tony Banks: I didn't even want to sing on my album, but I didn't want to sing. I did a video, which if you've seen it, it's very obvious that I don't really want to be doing that either. It's all that side of it that I really couldn't handle. I knew that I could probably sing it okay, but to be out there in front of something was not my nature. I'm just an introverted person, too self-conscious to do any of that. This wasn't really what I wanted to do. But we tried the song, This Is Love, I sang on that, did a video for it. Which was, as I said, it wasn't the greatest, but it was okay, I suppose.

Chris Welch: It's nice that you've done it though, you wanted to do. It's nice that you achieved it and did it.

Tony Banks: I suppose it's nice to have done it, isn't it? I didn't really repeat it. I only sang on one or two songs on later albums, but only songs that were quirky songs I thought that would be quite fun to do. After that, I decided to go back to trying to use real singers again because I think it makes the song sound better. Having had the luxury obviously of Phil and Peter, who are fantastic singers, singing my songs in the past, I didn't see any point of denying myself a good singer. So, that's why I tried to do again, with all the later albums

Chris Welch: And of course, in more recent years you've been writing movie music I think…

Tony Banks: Well not movie! No, I did do a bit of that, which didn't go very well either. I was originally hired to do the music to the film 2010, the follow-up to 2001. I met this guy, Peter Hyams, who was the director, and he'd really loved what I'd written for an obscure film called The Shout. He could actually sing it and it's quite difficult to sing and I thought, "He must really like it." Anyhow. So, I thought this was easy. I can write that sort of stuff in my sleep.

So, I wrote some stuff for him and he didn't like anything. His producer really liked the stuff, but he was not the man. It was quite underdeveloped almost, and just had ideas and stuff to where they would go and he didn't like it. I tried with two or three more pieces, didn't work. So, he basically ended up sacking me and hired James Horner, which was probably quite a good move actually.

What it transpired that everybody really wanted was an orchestral soundtrack, which he didn't say that to me. He wanted something more quirky. But anyhow, so that was my initial writing of that. I've written two or three films pretty badly, which didn't really come out very well. I took this song with the piece with Michael Winner called The Wicked Lady, which he got me. He worked on an album with I think John Paul Jones or something. He'd done a film with him, either that or Jimmy Page, one of them.

Chris Welch: Jimmy Page, I think.

Tony Banks: Yeah. He did a thing and I was suggested to him by the guy who worked for Atlantic and he said, "Well, why not try Tony?" I met him and we got on quite well. I had this piece that I hadn't used on The Fugitive or wasn't using on The Fugitive, because I'd given up by then, and just a little melody, which I thought was quite nice and he loved it.

Seven, Six, and Five. If I do another, don't ask me what it's called.

So, we used that as the basis for this film. I wrote a few other bits and pieces to go with it. But the film is actually terrible, but it has a fantastic cast. It's got Faye Dunaway, Alan Bates … you look at the cast and this is going to be great. It's most famous really now for a whipping sequence, where Faye Dunaway whips this topless girl who ended up being in Star Trek, The Next Generation*. So it's one out there for the afficionados. So, it probably gets more hits than it deserves.

But no, what you were trying to say when I was so rudely interrupted earlier on, is I've done orchestral music since. I've done three orchestral records since then. Seven, Six, and Five. If I do another, don't ask me what it's called.

Chris Welch: Did you do a score? You had to write all the arrangements?

Tony Banks: Well no. Basically I put demos to various degrees of elaboration, particularly the final one, Five, pretty defined a lot of the arrangement. I worked with arrangers and Simon Hale on the first one, and Paul Englishby on the second one, and Nick Ingman on the third one. They're all great people to work with and they put their own slant on it a bit, particularly Paul, I think put more in some ways with the second one.

To actually score for an orchestra it's a big job. You could do a simple score and a couple of pieces ended up pretty much how I did them. But when it comes to more complexity, I just thought I'd get the guys who know what they're doing who understand orchestra so much. Particularly on the second and third of those pieces I used them, they were the conductors as well, which helped a lot, because that meant that they could actually control the audience [six] in the way they wanted to.

So, it was a great experience. I think personally, they got better and better. But as was the case with my solo albums, they sold less and less. I think it's just difficult to get heard. I'm sure there are people out here in this audience who've written stuff that they think is great, just never had a chance of being heard. And that happens to everybody. It happens to be on these kinds of things.

I think you know that there are people out there if they heard this stuff would like it. It's just the nature of it, but they never hear it. But there's so much stuff out there, how are we really going to reach everybody? But I'm very proud of that, all of them actually, but the third one in particular, which really developed out of all the piano playing that was part of my demos. I used those as a template and put all the other orchestra parts on it. It meant that the final result was very close to what I'd originally intended. Whereas a couple of the other pieces earlier on sometimes went a bit adrift.

Chris Welch: I guess you had parents who loved classical music, I believe.

Tony Banks: Well, my mother did. My father was tone-deaf. He had no idea what was going on. He was very anti-music. In the early days when I used to play, we had a quite an open plan sitting room that you had to walk through to get upstairs. I used to play the piano all the time and I must've driven everybody mad. And I was playing endless Beatles songs and he used to go to through the room with his hands in his ears.

But of course later on when we started to do a bit better, he had a bit of eye for the girls. And when he went into the record shops, he could say, "That's my son you know." He quite enjoyed that. My mother though was musical, but she couldn't do anything. She had to have the music in front of her. It's extraordinary. Took the music away she couldn't play it, even though she played it 100,000 times.

It's a very strange thing that I'm the exact opposite. I hate having music in front of me, I just want to be able to change it a bit if I want to. But it was an influence on me and I was very much brought up on the classical music and was also the show tunes.

Chris Welch: Mahler?

Tony Banks: Mahler came a bit later actually. I remember having a conversation with Steve. We'd gone to see Death in Venice and we thought, this music is fantastic. What is it? At the time, Mahler was not a big name at all. There was a fantastic piece of music, Adagietto from the Fifth Symphony was used throughout this thing. What is this? And he tried to find it, and at the time, the music for Death in Venice hadn't come out. So, I went to the record library and I couldn't find it, The Fifth Symphony. I got hold of the Fourth and some other ones. It was extraordinary. But shortly after that, Mahler suddenly grew in stature until now he's considered one of the greats, but at that point he wasn't.

No, when I was talking about the show tunes is that I listened to when I was a child, my mother, we had all the Rodgers & Hammerstein in particular, and I love Richard Rogers. He was a wonderful writer. I love some of those. The other side of the group, was a bit suspicious of my augmented chords and diminished chords and stuff, which I like to slip in. I got them all from Richard Rogers really.

He's so good at using them within context so they don't sound unnatural.

The Sound Of Music, the main song, you've got a diminished chord within the first 10 seconds and I love that kind of thing. Beautiful melodies I think, and pretty good lyrics actually, it's not in those cases, it's not in rest of Hammerstein. So, there was that and obviously he has West Side Story, which was Bernstein..

Chris Welch: Bernstein.

Tony Banks: Also, My Fair Lady, which was Lerner and Loewe particularly I think. We had all these at home and I used to play them a lot, and I just loved that music. It just inspired me in a certain direction, as well as I love pop music. I loved all pop music at the time. But these show tunes just were at the time a little more elaborate and really moved me.

Chris Welch: Do you still enjoy playing the piano at home on your own?

Tony Banks: I do sometimes, I do play a bit. I sometimes feel I'm compelled to write if I don't feel like it. So, it's a bit strange. I don't play as much as I used to. There was a period of time when I would never stop playing and these days, I'll have periods. I have a day when I might play quite a bit and other days when I go out in the garden, do some weeding. It depends a lot on the weather I have to say. If it's fine weather then I'm outside. Been a very fine summer too, so it means there hasn't been much writing going on.

Chris Welch: I was thinking, I'm sure some of the members of the audience would love to ask you some questions as well. But just briefly, what was your greatest achievement with Genesis? What's your favorite record with Genesis, would you say? I know it's a hard question.

A lot of people say "I can't hear my own stuff", I see no reason not to do that.

Tony Banks: You have certain answers which I've given over the years, and I've always been very fond of Duke, I just thought it had such a positive, uplifting feel. I've always been a big fan of the song, Duchess, which is one of my favourites. It's concise, but it works on the bigger Genesis scale. I love Wind & Wuthering because it's got a lot of my stuff on it, I suppose. I do like my own music. A lot of people say "I can't hear my own stuff", Actors always say "I can't watch my own films". I listen to my own stuff, I think it's great. And I see no reason not to do that, and over the years there's been tracks, but I thought Wind & Wuthering and the early days we mentioned, Selling England By The Pound.

Then I also think that the last two albums were very good, particularly Invisible Touch and We Can't Dance. I think they sustained something in them that was really good. It's funny, I came across one of the songs on that recently. I was reading something and someone had mentioned the song, Since I Lost You, which I'd ignored at the time a little. For this I had written this chord sequence and played it on the piano, and then Phil warbled a lyric on top of it and stuff, and I'd not really thought about it very much.

I heard it and I thought this is actually really good. It was written obviously about the death of Eric Clapton's son, the lyric, and it's incredibly moving. It's very simple. I was quite, I thought that's pretty good. Kept it quite simple – simple chords, but not totally straightforward. And so you come across these things sometimes many years later which I had dismissed at the time, which come back and you think this is quite good. Well some of the other songs you thought were fantastic, are not so good.

Chris Welch: Sometimes when you ask a musician, have you retired and you say, "Oh, no I haven't." So, you haven't really retired from music, have you?

Tony Banks: You can always say you haven't retired as a musician, I think because no one really knows what you're doing. It's like authors, I'm between jobs. No, I would certainly not rule out doing something in the future. I've done this thing with Brian, who's here.

Chris Welch: I was going to ask you about it.

Tony Banks: It's just one of those things. Richard Macphail came down, he just mentioned that this guy, Brian, fancied the idea of doing something. He sent me this Jack Kerouac book, The Haunted Life, and a few possible lyric ideas. I just sat down and wrote something I thought was good in the spirit of the book. So, it's not part of what you might call wild progressive music, it's a mood piece if you like. That was only about a year or two ago. I quite like little projects actually. It's just also one where there's no responsibility to me, it's all on them. He ended up using my demo part because I don't know why – probably it was okay

Chris Welch: Did you approve of their music because they were recreating in a way they were inspired by British progressive?

Tony Banks: I listened to the rest of the album, there's a couple of really good tracks on there. To me it's a lot, I much, I enjoy it a lot more than I enjoy a lot of contemporary pop music. I don't know if I can tell you, but it was very exciting There's odd bits and pieces, but I get very muddled between all the girl singers that are out there. So, I don't find it musically not that interesting. The chords tend to be simple.

A lot of it's down to lyrics nowadays and things and arrangements and vocal performances. But the basic chord structures of things is people tend to be sticking very much with the old chord sequences and that doesn't really interest me very much. Whereas, you hear something like what Brian has done and they vary from that and that's good.

I'm sure there's lots of other people doing stuff out there too. But I don't have the same energy to go out and listen to stuff that I used to. When I was back in the '60s, I would try and seek out stuff and I remember buying one of David Bowie's first singles, a song called Can't Help Thinking About Me, because I hear it on the radio. I thought, "This is fantastic, I really like this."

Of course it didn't end up being a hit, but it attracted me to it and I followed him from then on. Obviously I was a big admirer all through his career actually. But that was something just because he was using chords in a way that was not totally normal and I thought that's great. It's no standard sequence here. This is doing something really…

Audience: So sorry to interrupt. We promised the audience a short Q&A as well.

Tony Banks: That's right.

Audience: Thank you for being here with us today. My question is about A Curious Feeling. Were any of those tracks outsourced or partial pieces from other Genesis material that you redeveloped?

Tony Banks: Not really. Apart from obviously the opening piece, From The Undertow, was originally constructed as part of an introduction to the song Undertow, although I completely changed it around and changed the emphasis. But you can hear the big theme in the middle of From The Undertow is obviously relates to the chorus of Undertow. Beyond that, no. It was just the next thing I wrote.

People often used to ask me in those day, "Do you keep something for Genesis?" It was just the next thing I wrote, those were all the next pieces. Had they been a Genesis album, a lot of them would've appeared on a Genesis album, I think. They would probably have sounded different because of different players, singers and all the rest of it.

But nothing was left over. That late '70s period was a very creative time for me, I was writing a lot of stuff and a lot of stuff was coming out of me. I don't think anything on that was really destined, even for the previous album.

Audience: You mentioned before Tony about working with Peter at Real World. There was a lovely picture of the two of you that was online. Do you ever foresee a time when you may work with Peter again creatively?

Tony Banks: I don't think… we've moved on a long way from that. We get on very well and everything, we still have a lot of shared visual tastes, but I just don't think it's something that would ever really happen. I don't see why in a way. Peter is doing his own thing and doing it very successfully. He doesn't really need me hanging about. I don't know. I never rule anything out with anybody. I've got no rules. I never thought anything that has happened to me musically in my life would've happened. So, you just accept what happens and where it leads you and see what happens. But I think I would suggest you don't hold your breath.

I've still got more hair than Peter, which is very important.

Audience: It must have been immensely pleasurable working with him all these years.

Tony Banks: I've still got more hair, which is very important. We still get on really well. It's funny, because he's a guy, 'cos he's got such incredible success over the years, he really hasn't changed much. Well, in self-confidence, but beyond that, he's pretty much the same bumbly guy he always was. He always had this advantage.

Peter and I used to do quite a lot of stuff together where I was mean and moody and slightly distant and a bit unappealing for that reason. He was bumbly and the girls just loved that, because he just seemed so vulnerable and he was also quite good-looking or very good-looking, I think. So, it was difficult having a friend like that in a way because he got all the girls, but we got on very well. We used to fight a lot when we worked together. He was someone he would labour over something for a very long time. Whereas, I've always worked to get everything finished as quick as I possibly could and get on to the next thing. So, that produced a bit of friction between us, but we wrote a lot of good stuff together, so it was a great time.

Audience: Thank you. Tony, you talked about and you talked all the way through the Genesis albums, and you stop and don't mention Calling All Stations. Where do you think that fits in the catalogue personally? The Dividing Line is one of my favorite Genesis tracks.

Tony Banks: I have mixed feelings about Calling All Stations just because we put it out with quite a lot of hopes, and it didn't really do what we might have hoped at the time. I think it was perhaps, I don't know, it's difficult to put your finger on it. When a thing is being successful, it has a glow about it, and when a thing has not been quite as successful, it has a slightly darker mood about it. I think a lot of the songs are great on it, I think some of the playing on it is really good. I think particularly, Nir, the drummer was excellent and I was quite pleased. What I quite enjoyed from my own point of view actually, was I took quite a few adult themes for lyrics.

I wrote about divorce, which I don't know much about. I wrote about terrorism, I wrote about addiction. That one didn't make it on the album unfortunately, but it's a good song 'I've run out of time', and it was quite fun to go there. Having been a person over the years, I'd always written fantasy stories, even if I was telling something quite serious like One For The Vine, I would dress it up in a little fable, if you like, rather than being direct about it.

So, I was quite pleased. I particularly thought that the one about, well, the first half of One Man's Fool, which is all about terrorism, about bombs and stuff, which sounds like it was written after 9/11, but of course it wasn't, it was written before that. It was written primarily about the bombing in Manchester is what I was thinking of.

But it is just so funny, those of you who have not listened to the song, give it another listen and listen to the lyric, because I was quite pleased with that. I thought it worked quite well. Second half of the song doesn't really live up to it, but the first half was great.

Audience: There's a lady called Ursula from Northumberland who asked, are you going to go up north? Newcastle?

Tony Banks: If I get invited there yeah. Nothing against it. I haven't really done many of these things. I did one in Cheltenham when one of my pieces was done down there. And I did that to actually just talk. It was weird in a way. But you do so many interviews and things over the years that I do think consciously you repeat yourself. Before I came to do this, I listened to one or two earlier things just to see what I used to say. I thought 1978 I found something that someone had discovered that I'd done in Malmo, and I thought what a prick. It sounds, I'm a bit kind of arrogant. But it was great.

I also said something which was strange at the time that I didn't think I was not political. I didn't think about politics at all. And of course now I do quite a lot, I'm quite into politics and the rest of it.

So, I think you do change and that was about 50 years ago, so I suppose you are allowed to change. I've mellowed a bit, I think. I also watched a little bit of one I did with Phil, it must have been around the time of Invisible Touch, which was quite nice with a bit of banter between us and everything. It's nice to remember Phil like that, because it's not quite the same now, it's a bit different. But we had a great time together, so it was nice to go back to that.

Audience: Thank you. Tony, you said in answer to Chris that with your solo material you're frustrated that not more people have got to hear it. If you had a magic wish and there was one track you could make sure everybody did hear from your solo works, which one would it be? If I can just shoehorn in, I think my choice would be Lion of Symmetry with the wonderful Toyah voice singing on it. What would your choice be of a song that everyone would hear?

Tony Banks: There's too many. Lion of Symmetry is something I was very proud of at the time actually, and it was great fun working with Toyah, because up to that point, she hadn't really stretched her voice very much that far. She worked a lot with various people. I just thought the idea of making her go for it a bit and it worked really well. She was lovely to work with, because I wrote a lyric, she wrote one lyric, which I thought was okay. I wasn't that concerned. It sounded okay to me, and she said, "I don't like it," and she wrote a totally new lyric after that, and I think she belted it out. Well, I think particularly the middle part of that is really strong. I agree, I like it.

I don't know. One of my favourites is I wrote the instrumental piece The Waters Of Lethe, I have to say. I just felt … the chords in the middle there may have a little bit to make [?] us through, but it just sounds so good. But no, I like, I don't know. What others do I like Chris?

Chris Welch: I have no idea.

Tony Banks: I liked … I cannot remember what it's called now.

Chris Welch: Will I give you a really bad review?

Tony Banks: Yeah, you probably will. But God. I'll Be Waiting. It's a song I like a lot on Bankstatement. But obviously I like An Island In The Darkness, which I wrote almost as a piece from recalling my past in a way. I thought that let's just do one, I'm going to do one, where I just allow myself to just go anywhere really.

A lot of it was improvised, the beginning bit and the bit in the middle. The bit in the middle actually, it was almost totally improvised. I had to re-learn how I played because I wasn't quite good enough and that took quite a bit of learning. The idea of using, which I suppose we'd done it for Firth for Fifth, using the theme quietly and then doing it loud appealed to me because it worked so well on Firth the Fifth.

The melody I'd written basically for flute and piano. It was Steve's idea to do it loud, he said, "Let's do it loud, you play Mellotron, Phil will play the drums and go for it." I thought this is going to be such a cliche, we can't do this.

Anyhow. We did it and I thought this sounds fantastic. So it gave us a pattern. When it came to An Island In The Darkness, I thought, well I'll do that again a little bit, use the little melody, and then play it again with guitar lead, with Daryl who played a beautiful guitar solo, I think on the top of the end of a 15-minute song. I think very much in the tradition of early Genesis, it was designed and made that way I suppose. I needed to get it out of me. And I thought that was possibly, I wasn't sure I was going to do anymore after that, and I thought it was a good way to end it all really. But I think it's a good piece, I think it works really well, so I'm proud of that one.

Every time I say one piece, I think of others. There are simpler pieces – I mean I wish we could have made I Wanna Change The Score into a hit because I think it could have been a hit, and that would've made quite a difference at the time. But the record was on, a lot of people were very keen on it, but no DJ would risk playing it, even though it had Nik Kershaw on that, who was quite hot.

Chris Welch: Would you like to go on the road again and play live music with a band?

Tony Banks: Would I?

Chris Welch: Yeah. Tonight.

Tony Banks: I've never been on the stage with either visual or film. It's not my forte. That's not really where I'm happy. I know Steve is got quite good at it, don't get me wrong. He would say it wasn't really the natural thing he wanted to do. But it's not something that comes for me. Writing is what I really enjoy and when I can do that and get stuff out, I want to do it.

I don't mind being part of that combination. The trouble is, Phil is probably not really going to be in any shape where he can play live again. You mentioned Peter, but I don't think Peter needs us unless we did something, an old retrospective thing, which I think is very unlikely. And also it does take quite a lot to get the whole thing together. If you want to play live and do some of these pieces which have never been played live on the road before ever in a sense, it's a lot of work to try and get it all so that it does work. You've got to get personnel, musicians and people and oh, God, I feel very tired already actually.

Audience: Hello. I'm over here. I have grown up on Genesis, listened to it all my life. My favorite band and Firth of Fifth is one of my favorite pieces of all time. Could you please tell me about how you composed that intro?

Tony Banks: That's a very good question. I had a little piece I was going to possibly use on Foxtrot, which involved a piano thing. It was some element of that and we decided not to use that. I don't really know how it ended up the way it did. I just got that first phrase and I thought, well this is quite exciting. And I didn't worry about it. I've never been much of a time signature man anyhow. And didn't really worry too much that I wasn't keeping to four-four or whatever and it just developed. I honestly can't say why it ended up like that. One thing led to another and that's how it turned out.

Chris Welch: The magic of music, you never know quite how it will end up …

Tony Banks: Well, sometimes it is. Most of the time you don't know whether you've written anything good or not. Again, I was pretty proud of that when I'd done it, but it was trying to convince the band that it should be there. The best way of making the band was, it was actually to do a version of it with the band playing as well, which is what we did in the middle of it. Which I thought was quite fun to do because it was like a big band thing because I going, things happening all over the place.

So, the whole song ended up in three pieces that I didn't originally see in the same section. I had a beginning, I had a flute melody, and I had a basic song. I think the others, in order to get them out the way, said, "Let's go all the way". And so that's what we did really. Once we did this idea of doing the flute solo loud, it suddenly showed a whole way you could go so it could build to this big, big climax and then come back after to the verses at the end. For me, that guitar solo is one of the strongest moments of early Genesis and I think Steve played it beautifully, but I have to say: it is my melody.

If you put Peter on stage at the O2, it would change the emphasis!

Audience: My question is, Tony, did you ever consider inviting Peter Gabriel on stage for the last ever gig at the O2?

Tony Banks: It was mooted. But I think it was a strange moment for us because this was the end of the whole career really. It just seemed to me, if you put Peter on stage, it would change the emphasis to such an extent, that we felt it was the wrong thing to do. I had an occasion of this when shortly after Peter left the band, we did Madison Square Gardens and Peter came on when we did an encore of The Knife. And I remember coming on stage and all the people around me, the Atlantic people, the rest of them were congratulating Peter on the show, on what he did. I thought it's become such a strange change of emphasis, you've just come off-stage, you played a good show and people liked it and everything.

But the only thing they remembered was that Peter came on at the end. I think in the case of The Carpet Crawlers that was why. I can understand people thinking it's relevant, it's a song from his era and everything and it would've been nice in its own way. But I think as a final show it just would've been a bit strange.

Chris Welch: I was just going to say, what was the funniest thing that ever happened to you while you were still with Genesis?

Tony Banks: You never should ask questions like that. There's been a few. One of my favourite ones actually was at the end of Supper's Ready, when we did Seattle, which was the last gig on the tour. Our manager thought wouldn't it be funny to have three strippers come on stage? It was extraordinary. To be honest, these girls, how should I put it? Not the most svelte. I was there playing and Supper's Ready was you know, a big song, this is fantastic stuff. And suddenly these girls walked in front of us and I'm like, "What the fuck is going on?" They circled round Peter and the audience of course thought this was obviously part of the act we always did. God knows it was very, very strange.

And then the other one, which I will mention as well, because there's slightly more pathos in this, was I mentioned the Besançon show, that was the final show we did and we knew it was going to be the final show. So, the crew didn't know that this was it and that Peter was going to leave and everything like that. So, they wanted to do one of their tricks.

I don't know if anybody saw the live show, but there was a moment just before the final bit, which is one of the best moments in the show, where Peter on one side and a dummy looking like Peter on the other side in strobe lighting and you didn't know which was which, and that was very effective. So, then when Peter actually moved, it was very, very strong. So, what they decided to do is one of the roadies, my roadie as it turned out, decided to go on instead of the dummy naked. I mentioned that those girls weren't that svelte, well this chap was not that svelte either. It was hilarious.

It was quite weird, because the sound people, my wife and all of those who were in the control room, control box and watching stuff and everything, they knew it was the last show. So, it was the last thing you wanted was this extraordinary moment as the final thing of the final show done with Peter. That was it. So, sort of funny, but it wasn't really that funny.

After the interview, the Band Rocking Horse Music Club performed on stage …

You can discuss this Q&A session with other fans in our forum in this thread.

Transcript: Stefano Tucciarelli, edited by Paul Kingsbury and Christian Gerhardts

Photos by Volker Warncke and Ibelise Paiva